The Westview School Blog

Progress, Not Perfection: Understanding Growth in Neurodivergent Learners

When Ceara Wainright-Herod, Upper School Principal at The Westview School, addressed parents at a recent Westview EDU, she began with a simple question: What does progress really mean?

The answer, she suggested, has little to do with report cards. With nearly two decades of public education experience, Herod has worked with students across the autism spectrum, neurodivergent and neurotypical learners alike. One message, she says, has remained constant: growth differs for every child and rarely follows a straight line. Her Westview EDU session, "Progress, Not Perfection: Understanding Growth in Neurodivergent Learners," directly challenged the common belief that progress is only about grades, reinforcing that growth at Westview is about the whole child.

Beyond the Report Card

“Dictionary.com defines progress as growth and development, continuous improvement, a movement toward a goal,” Herod said. “Nowhere in that definition do you see the word ‘grades.’ Nowhere does it say ‘academics.’”

For many parents, grades carry enormous weight. A low test score can cause worry; a good report card offers reassurance. Herod believes equating grades with progress overlooks how children, especially neurodivergent ones, develop.

“There are so many skills your child is building that don’t show up on a report card,” she said. “Independence. Confidence. Curiosity. Emotional regulation. Problem-solving. Those are real gains. They deserve celebration.”

The Myth of the Straight Line

One important part of Herod’s message was the reminder that no child grows in a straight, predictable trajectory.

“Growth includes plateaus, regressions, and spurts,” she said. “That’s not a flaw, that’s development.”

She encouraged parents to recall their own school years: subjects that came naturally, years that were a struggle, moments when understanding clicked. Children experience the same uneven progression. Neurodivergent learners may show this more, but the pattern is universal.

“A single low grade isn’t the story,” she said. “It’s one data point in a much bigger picture.”

Three Lenses for Understanding Growth

Westview uses a holistic, strength-based model to understand student growth, which Herod believes offers a more accurate and compassionate view. The model includes three domains:

ACADEMIC GROWTH: This includes the traditional markers such as reading, writing, and math, as well as the quieter signs of learning: beginning an assignment independently, asking questions, showing persistence, and building comprehension over time.

“Academic growth isn’t just the score,” Herod said. “It’s effort, curiosity, and the willingness to try again.”

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL GROWTH: This area encompasses emotional regulation, self-awareness, confidence, and peer relationships. For many neurodivergent learners, these skills take time to develop.

“When children don’t know something, we teach,” Herod emphasized. “That includes how to deal with frustration, how to express emotions, and how to calm their bodies and minds. These are learned skills.”

EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONING: Organizing materials, managing transitions, following routines, and using coping tools are key here.

Herod recalled watching Westview Middle School students confidently open their lockers this morning, something that had taken weeks of practice and patient guidance.

“It was incredible to witness,” she said. “Routine, structure, and repetition work. When students succeed, their pride is enormous.”

The Role of Discomfort in Growth

Herod repeatedly emphasized: growth is uncomfortable for children and adults.

She shared several quotes with the audience, including Brian Tracy’s well-known line, “Growth and comfort do not coexist.”

She explained that children resist new challenges not because they can't succeed, but because the discomfort can be overwhelming.

“Those big reactions you see? The protests, the tears? That’s fear,” she said. “They don’t yet have the words to say, ‘This scares me’ or ‘This is hard for me.’”

Parents can help their children manage discomfort by modeling coping strategies.

“Tell your kids, ‘I’m nervous about a meeting today, so I’m taking deep breaths,’” she suggested. “Show them what managing big feelings looks like. That vulnerability is powerful.”

Rethinking Assessment

Twice a year, Westview uses standardized MAP Growth assessments to gather academic data, but Herod urged parents not to put too much weight on the scores.

“These tests aren’t designed specifically for neurodivergent learners,” she explained. “Some students sit through 45 questions in one session. If they’ve had a tough morning, if they’re distracted, if they’re overwhelmed, that score isn’t representative of their true understanding.”

Instead, the school emphasizes teacher observations, student reflections, and classroom work samples for a complete picture of progress.

“Tests matter,” she said, “but they don’t define your child.”

A Partnership Between Home and School

Herod stressed the importance of partnership: parents know their children best, and teachers see them in structured settings. Together, families and educators provide continuity that helps students thrive.

She encouraged parents to share what works at home, ask questions during conferences, and communicate openly with teachers about concerns.

"We are a village," she said. “Your insight helps us support your child, and ours helps you support them at home. Working together, students make meaningful progress.”

A Final Story

Herod ended with a personal story. At four, she struggled with separation, sensory overwhelm, and fear, crying daily at her first school as staff grew frustrated.

“I wasn’t dramatic. I wasn’t a troublemaker. I was anxious,” she said. Her mother moved her to another school where she felt safe and welcomed. She never cried again.

"I share that to show what safety and belonging can do for a child," she said. “That's what we want for your children at Westview: a place where they feel loved, supported, and celebrated on all days.”

The Message Parents Took Home

By the end of the session, one message stood out: progress is not about achieving perfection, but about each child's unique, steady growth at their own pace.

“Your children are not victims of their challenges,” Herod said. “They are victors. And every day, we see their victories.”

--

Ceara Wainwright-Herod, M.Ed. is the Upper School Principal at The Westview School. She has over 18 years of experience in public education, having served as a teacher, specialist, and assistant principal in public school system. Her work is grounded in student-centered learning and inclusive leadership. Ceara holds a master’s in Educational Leadership from the University of Houston–Victoria and has extensive experience supporting students across the autism spectrum and has collaborated with families and specialists to design individualized plans that meet each learner’s needs.

This blog post was adapted from the presentation given during WestviewEDU on Thursday, November 13, 2025. WestviewEDU is an education series presented by The Westview School for parents and caregivers of children with autism. For a complete list of WestviewEDU sessions remaining for the 2025-2026 academic calendar year, visit The Westview School online.

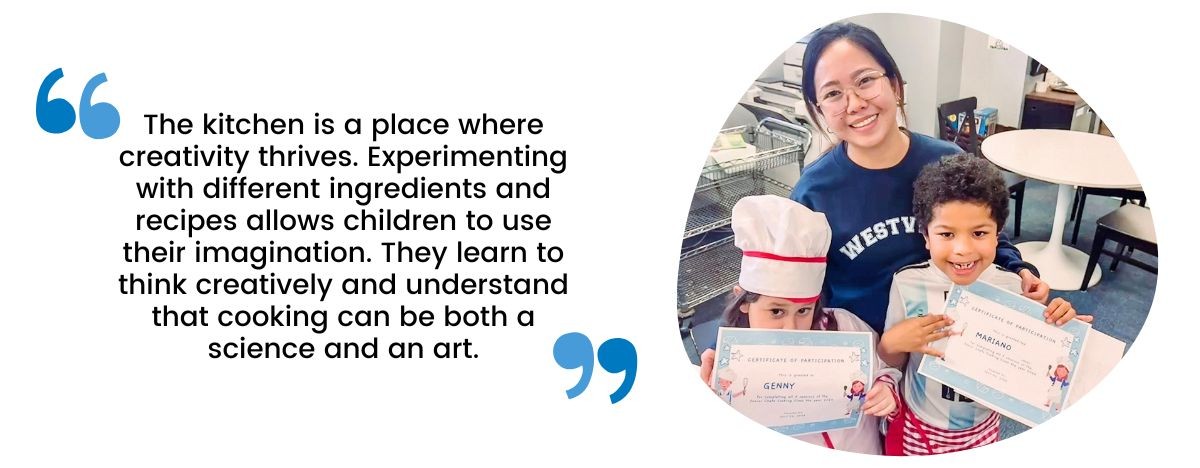

Cooking Up Connections: The Magic of Family Time in the Kitchen

Parents are often looking for recommendations for fun family activities that could enrich their child’s life. Often, the best options can be found right at home.

Have you ever thought about involving your child in the kitchen? Activities such as preparing dinner, making a snack, or trying out a new recipe together can be a great start!

Cooking Skills and MORE

We all know that cooking teaches essential skills like measuring ingredients, following the sequence of steps in a recipe, and using various kitchen tools and equipment. Cooking provides an opportunity for children to learn how to handle utensils, chop vegetables, and stir batter. However, cooking offers far more than just the ability for your child to prepare meals for themselves and the family.

The kitchen is also an excellent place for sensory exploration – touching sticky textures (like dough) and experiencing various temperatures. Children with sensitivities to touch, taste, and smell, including those often described as "picky eaters," can benefit from this exposure, provided it allows them to explore at their own pace. This multi-sensory experience can expand their palate or help accommodate their specific support needs. For example, they may discover that wearing gloves can help their ability to handle certain textures.

The kitchen is not just a place for culinary adventures, it's also a classroom for safety. It's a perfect setting to teach children about the importance of being aware of extreme temperatures, sharp objects, breakables, and heavy items.

If you have concerns about kitchen safety, rest assured that there are kid-friendly tools like knives and scissors, non-slip cutting boards, and step stools available. You can gradually introduce them to heated tools, based on your and your child’s comfort level. This is also a great opportunity to demonstrate how to safely use the oven, stove, or air fryer.

The Beauty of Cooking at Home

One of the best things about cooking with your kids in the kitchen is that you can make this a space for them to explore, make mistakes, and learn in a safe and familiar environment. When things get messy, spills happen, hands get sticky, or something breaks accidentally, allowing them to experience the natural consequences, teaches cause and effect. Initially, holding back immediate corrective feedback and allowing them to do it themselves allows them to learn and adjust. This approach builds their confidence and kitchen skills and reinforces your role as a trusted adult they can rely on for guidance.

These moments in the kitchen become cherished family stories, offering a chance to share the joy of creating something. Children witness firsthand how to communicate and how cooperation leads to a delicious end product. When families cook together, they learn to work as a team.

As children grow more comfortable in the kitchen, they gain independence. Learning to prepare meals for themselves is an essential life skill throughout their lifespan. The confidence they earn from these experiences extends beyond the kitchen and may contribute to overall self-esteem. If cooking is an accessible skill for your child, there are benefits to starting early and introducing them to the kitchen, especially if this is an area of interest.

By making cooking a shared family activity, you not only impart essential life skills to your children but also create a nurturing environment. So, roll up your sleeves, grab those aprons, and enjoy the many rewards of cooking together!

---

Theresa is a Registered Occupational Therapist with experience working with children, youth, and adults with neurological differences in the private school, clinic, and community settings. She received her Doctorate Degree in Occupational Therapy from The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Prior to becoming an occupational therapist, she worked in the field of Applied Behavior Analysis as a Registered Behavior Technician. She is also a writer and consultant who offers her specialized knowledge to websites and companies serving the neurodiverse community.

Visual Supports to Build Independence: Teacher Techniques That Transform Learning

At The Westview School, we believe that fostering independence is a cornerstone of helping children with autism thrive academically, socially, and emotionally. One of the most effective tools in this journey is the use of visual supports. Visual supports use images, symbols, or cues to help students process information, communicate clearly, and navigate their day. Some examples of this include picture schedules, checklists, social stories, timers, and task cards.

From managing daily routines to enhancing emotional regulation and problem-solving, visual supports empower students with confidence and autonomy. Westview teachers and administrators integrate these strategies into their classrooms every day. Each approach reflects the creativity and dedication of Westview staffers to ensure every student has the tools they need to succeed.

Morning Checklists: Starting the Day with Independence

Christine Reilly, Lower Elementary Teacher

Executive functioning skills, such as organization and time management, can be challenging for children with autism. Visual checklists provide a structured approach to these challenges. In Lower Elementary, students start their day with a visual checklist displayed on the board detailing morning expectations. For example, a picture of a backpack represents hanging it on a hook. As the year progresses, these picture prompts are gradually replaced with words, and eventually, students complete tasks independently without visual assistance.

"This approach not only creates a predictable environment but also reduces anxiety and fosters a sense of accomplishment," says Christine Reilly. "Students feel confident knowing they can take responsibility for their morning routine."

Transition Cues: Easing the Shift Between Activities

Trevie Stone, Lower School Physical Education Teacher

Transitions, particularly away from preferred activities, can be challenging for many students. Leaving the motor room can often be a tricky transition. Visual timers, such as the TimeTimer™, paired with verbal countdowns, help students understand the abstract concept of time.

"I might say, 'We have five minutes left. What would you like to do before we leave?'" explains Trevie Stone. "Picture cards are another helpful tool. A small picture of the next activity or location can be a tangible reminder, helping students anticipate what's next."

The physical setup of the environment also supports transitions. Designated line-up spots and shoe cubbies act as visual cues for students, creating a smooth and predictable flow from one activity to the next.

Innovative Visuals for Younger Students

Amanda Warley, Prekindergarten Teacher

In Prekindergarten, visuals are everywhere—on the walls, at tables, and in task instructions. Amanda Warley recently introduced a portable photo printer to create instant visual aids tailored to her students' needs. "If a student prefers blocks over trains, we can immediately update our visuals to reflect that," she shares.

Amanda also uses visuals to prepare students for new experiences. For example, before practicing for the holiday program in a different building, she printed a photo of the location. “Having a picture helps students process what to expect, reducing anxiety. These personalized visuals make all the difference in fostering understanding and comfort.”

Step-by-Step Task Cards: Building Independence in Learning

Serena Gaylor, Middle School Language Arts Teacher

Breaking down tasks into manageable steps fosters independence and encourages self-assessment. "In my classroom, students always have a 'to-do' list and an 'after I'm finished' list displayed on the screen," says Serena Gaylor.

Recently, during a poetry unit, students followed a criteria-based checklist to evaluate their work. "This allowed them to independently assess their poems, identify areas for improvement, and ask more specific questions," Serena explains. "Step-by-step guides give students the tools to take ownership of their learning and build confidence in their abilities."

Visual Supports for Emotional Regulation

Sally Schwartzel, Lower School Principal

Visual supports also play a vital role in helping students manage their emotions. Tools like visual schedules, checklists, and social narratives provide clarity and predictability, reducing anxiety. "When students know what to expect, they feel more in control of their day," says Sally Schwartzel.

For emotional regulation, visuals can help students identify their feelings and choose appropriate coping strategies. “If a student feels frustrated, visual supports remind them of what they can do—like taking deep breaths or asking for help. This empowers them to navigate challenging moments with greater confidence.”

Empowering Students Through Visual Supports

Visual supports are more than tools; they are bridges to independence, confidence, and self-advocacy. At The Westview School, we take pride in using evidence-based practices to meet our students' unique needs. By integrating creative and personalized strategies, our educators ensure that every child can shine in their own way.

Want to see these approaches in action? Visit our website or connect with us on Instagram and Facebook to learn more about how we are empowering our students every day.

Making a Language Connection: Gestalt Language Processing in Autism

Language is a foundational tool for human connection, but how it's acquired and processed can vary greatly. For individuals on the autism spectrum, language development can sometimes follow a distinctive route called Gestalt Language Processing (GLP). One of the key features of GLP is echolalia—repeating phrases or language chunks they've previously heard. This behavior, sometimes misunderstood as meaningless repetition, actually plays a significant role in language learning. Understanding the nuances of GLP and echolalia can open up new ways to support those with unique communication needs.

What is Gestalt Language Processing?

Gestalt Language Processing is a way of learning and using language where individuals process larger language segments, such as phrases or sentences, rather than focusing on individual words. This approach is grounded in Gestalt psychology, which suggests that our minds perceive things as whole units rather than isolated pieces. For many neurotypical children, language starts with single words and gradually builds into more complex sentences. In contrast, Gestalt language processors often begin by learning language in chunks—phrases they've heard in TV shows, songs, or daily conversations. These segments are memorized and repeated verbatim as the initial step in their language journey. Over time, they learn to break down these chunks and use them flexibly to create novel sentences.

The Role of Echolalia in Gestalt Language Processing

Echolalia, the repetition of previously heard words, phrases, or sounds, is often observed in early GLP language stages, particularly among autistic individuals. There are two primary forms of echolalia: immediate and delayed. Immediate echolalia involves the instant repetition of recently heard phrases, often as a way of processing language or mirroring the emotions conveyed in the interaction. For instance, if someone asks, "Do you want to go outside?" an individual might respond by repeating, "Do you want to go outside?" instead of directly answering. Delayed echolalia, on the other hand, occurs when phrases heard in the past—sometimes days or weeks earlier—are recalled and repeated. This is commonly referred to as scripting. These phrases might stem from movies, TV shows, or previous conversations and can be used to express emotions or communicate specific needs. For example, a child feeling overwhelmed might say, "Let it go!" echoing a familiar Disney lyric to signal their need for a break.

Echolalia as a Key Part of Language Development

Contrary to being a random or meaningless behavior, echolalia is essential to language development within GLP. Instead of focusing on single words, individuals initially store entire phrases as building blocks for language. Through repetition, they start to understand social cues and language patterns. Eventually, they begin to manipulate these stored phrases, breaking them down into individual words and allowing them to construct unique sentences.

Echolalia serves several roles: it helps individuals learn the rhythm and structure of language, allows them to express emotions and experiences that resonate deeply, and sets the foundation for more flexible, self-generated language. For example, a child who frequently says, "It's time to go to bed," might eventually repurpose the word "bed" in new sentences, like "I want my bed," demonstrating growing independence in their language use.

The Connection to Autism: Why Autistic Individuals Often Use Echolalia

Echolalia is especially common among autistic individuals, who frequently use it as a primary method of communication early on. There are several reasons for this. Autistic learners often have an exceptional ability to recognize patterns, and language chunks can serve as familiar patterns they can recall and apply in specific contexts. Additionally, many autistic individuals experience heightened sensory awareness, which may cause them to focus on the tonal and rhythmic aspects of language over individual words. This focus on auditory "wholes" makes echolalia an effective tool for processing language patterns.

Socially, echolalia can bridge the gap between an autistic individual's inner world and the expectations of the social world. By repeating phrases they've heard, they are engaging with language in a way that allows them to participate in social interactions, even if it doesn't follow traditional conversational norms.

Supporting Echolalia and Language Development

When viewed through the lens of GLP, echolalia is not a behavior that needs "correction" but rather a meaningful stage in language development. For those who work with or care for individuals using echolalia, there are several ways to support their language journey.

Acknowledging echolalia as a valid form of communication is essential. Rather than dismissing repeated phrases as meaningless, it's helpful to consider them within the context of the individual's emotions, needs, or attempts to participate in conversations. Providing varied, emotionally engaging language experiences can enrich the language they're absorbing and increase the variety of phrases they can use over time. Patience is key in supporting their language development; each individual progresses at their own pace, and allowing them the freedom to navigate language in a way that feels natural to them is crucial.

Conclusion

Gestalt Language Processing provides an invaluable perspective on how some autistic individuals develop language, highlighting the significance of echolalia as a natural part of that process. For those who process language gestaltically, echolalia is a bridge from memorized phrases to flexible, self-generated language, where each stage supports the next.

Understanding GLP and the role of echolalia allows us to see language development as a spectrum of unique pathways, each worth supporting and celebrating. Embracing this approach not only provides effective support but also empowers individuals to communicate in ways that feel authentic to them, fostering genuine connection and self-expression.

References

Blanc, M. (2012). Natural language acquisition on the autism spectrum: The journey from echolalia to self-generated language. Communication Development Center, Inc.

Peters, A. (1983, 2021). The units of language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Prizant, B. (1982). Gestalt language and gestalt processing in autism. Topics in Language Disorders, 3(1), 16-23.

Carlie Krueger, MS, CCC-SLP is a Speech-Language Pathologist at The Stewart Center at The Westview School. She graduated Summa Cum Laude from Utah State University with a B.S. in Communicative Disorders and Deaf Education and obtained her M.S. in Communication Sciences and Disorders from New York University. She strives to practice within a neurodiversity-affirming framework that centers self-advocacy and authenticity for her clients. Carlie has been working full-time as an SLP at The Stewart Center at The Westview School since 2022. If you or your family are interested in learning more about the services The Stewart Center provides, visit us online at The Stewart Center.

From Tantrums to Triumphs: Behavior Strategies at Home and Beyond

Understanding behavior, whether at home or in the community, can feel overwhelming, but it all boils down to one simple fact: behavior is just any measurable action. In this blog post, Sally Schwartzel, Lower School Principal at The Westview School, shares practical strategies for managing behavior by focusing on what we can control—our own actions. From offering choices to teaching replacement behaviors, these insights help parents create more positive interactions with their children. This post was adapted from her presentation for September WestviewEDU.

Behavior: It Is What It Is

When thinking about behavior in the home and community, there are many topics to cover – everything from self-help skills to attending a group function with peers. However, this wide range of topics can all be addressed by looking at behavior for what it is. It’s just behavior! Behavior is any measurable, observable action. Behavior is anything from waving hello to someone to hitting a friend.

The most important thing to remember is that we cannot change the behavior of others. This can be SUPER frustrating! BUT, there are things that we can change. Changing what we are doing, in turn, will change the behaviors of others. To figure out what to do before or after, we need to know “Why” the behavior is occurring. The “Why” is also called the “function” of the behavior. Don’t worry – there are only two main reasons why behaviors occur. PSA: This applies to all people, not just our kids. All of us exhibit behaviors (positive or negative) because we obtain or escape something. Many times, we work for a paycheck (obtain). We also push the snooze button on an alarm – to escape the noise… and the waking up part! To change behavior, we have to change what happens before or after it happens – which is something we can control.

Changing the Before and After

So, what can we do before a behavior happens to prevent it? My favorite is offering a choice – with a catch. The choice isn’t “Are you ready to do your homework?” The choice is “Do you want to do your homework now? Or do you want to do your homework in 5 minutes?” This gives the option to make that choice - but within your parameters. My second biggest recommendation is to frontload expectations. Give your kids a visual schedule or a checklist. Set up a routine. The more our kids know what to expect, the fewer surprises for everyone involved! Think about what a “to-do” list does for you... the schedule/checklist is their “to-do” list!

What about after a behavior occurs? If a person is still exhibiting a behavior, they are either obtaining or escaping something. For example, if a child throws a tantrum in line at the grocery for a candy bar and gets a candy bar, next time, it’s really likely that the child will throw a tantrum again. If a child rips up their homework and doesn’t have to complete it, it will likely get ripped up again. To break that pattern, we need to change what happens after. We can power through the line at the grocery store with the child kicking and screaming. We could have extra copies of the homework or ask for a laminated copy that can’t be ripped. Seems easy enough, right? WRONG. Sometimes, the tantrum in the line in the grocery store is too big. Sometimes, the ripping of homework after a long day is the final straw at the end of a really long day. The missing piece is teaching our kids what to do instead of the challenging behavior.

Teaching Replacement Behaviors

The “what to do instead” is called a replacement behavior. Replacement behaviors get our kids what they want (or don’t want) in a more appropriate way. If we set the expectation at the grocery store as “If you do not throw a tantrum and you ask for a candy bar,” you will get it. If, during homework time, the expectation is that the child can ask for a break or ask for help, that is a much better behavior than ripping it up.

You’re probably thinking, “So I have to let my child get a candy bar every time? Or let them not do their homework?” The answer is… well, kind of. This is only in the beginning while you are teaching those replacement behaviors. Once the child learns they do not need to exhibit those inappropriate behaviors, you can start taking steps back or fading support. For example, the new expectation is “If you do not _____, you can get a snack this time in the line and a candy bar next time.” The expectation can be set at the beginning of the grocery store trip that a candy bar isn’t an option this time, but these three different yummy snacks can be asked for. When it comes to homework, maybe the child needs to write their name on the homework before asking for a break. If the child learns to ask for help, maybe you give them the answer to the first part and then have them complete the rest on their own.

Simple Long-Term Tips for Success

Behavior is so easy and so complicated at the same time. The best advice I can give (learning from different parents throughout the years) is to do what you must to keep your sanity. Tip for doing that and still working behavior to your advantage? Having your child comply with the tiniest directive before giving them a preferred item or activity will save your life in the future. I have had some parents, in order to keep their sanity, have their child simply push in a chair, clear a dish, etc. before iPad time. It seems so small, but it will really help out in the future!

Sally Schwartzel is the Lower School Principal at The Westview School. She brings a wealth of knowledge and experience to The Westview School, having worked for over 18 years in Katy ISD as a special education teacher in specialized autism programs and then as a leader at the district level for autism and behavioral programming. She holds a Master’s Degree in Special Education with a focus on Autism and Developmental Disabilities from The University of Texas. She is a Certified Teacher and a Board Certified Behavior Analyst. She has co-authored and co-presented on relevant topics such as Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports and Autism Support and Intervention Program.

This blog post was adapted from the presentation given during WestviewEDU on Thursday, September 5, 2024. WestviewEDU is an education series presented by The Westview School for parents and caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. For a full list of WestviewEDU sessions for the 2024/2025 academic calendar year, visit The Westview School online.

Executive Functioning: Air Traffic Control for Your Brain!

Do you know people in your home or classroom who always lose their belongings, forget important items, get lost from the kitchen to the bedroom, run chronically late, or just generally seem like a "mess?" Weak executive functioning could be to blame!

Executive functioning is a general term that refers to our mind’s mental manager or the cognitive processes that regulate our thinking and behavior. While there are many models of executive functioning, most include the individual’s ability to generate ideas, initiate or begin a task, stick to and finish a task, flexibly problem-solve, shift from one idea or topic to another, inhibit our impulses, ignore distractions, regulate attention, regulate our behavioral and emotional responses, use feedback to guide future behavior, select relevant goals, organize materials, hold information in mind until needed, and more. I like to think of our executive functions as air-traffic control for our brain or as the conductor of the mind’s orchestra.

When all is well, cognitive processes flow smoothly, and behavior fits the situation as expected. When there are problems… well, just imagine the airport with poor air-traffic control! Executive functioning is needed for all aspects of life. Socially, we need executive functioning to help us regulate our behavior and emotions when we are upset. After all, throwing the board game when we are losing is frowned upon…, particularly in adolescence or adulthood! We spend a great portion of time controlling our impulses to speak out in school or a meeting, to refrain from spending too much money, or even overeating. Executive functions help us to arrive on time, prepared, and with a plan for how to behave. They are also critically important for academic success. Not only are executive functions needed for decoding written text, reading comprehension, solving math word problems, and long division, but they are also needed to be an organized, efficient student who remembers homework and can plan for projects and tests. These days, if you are not in the right place, with the right things, at the right time, it is difficult to be a good student, no matter how bright you are! In fact, being in the right place, with the right things, at the right time is the very basis of holding a job.

When there is executive disfunctioning, life may feel chaotic or unproductive. The child or adult may experience social, academic, or employment difficulties and/or problems in the home. The good news is that executive functions are thought to be able to be developed or strengthened. These skills begin developing in infancy as babies learn to wait to have their needs met. They really come ‘on board’ in the brain around age two as children learn they are active agents in their own world. Beyond that age, executive functions are thought to keep developing into young adulthood. Just as they can be strengthened, executive functions can be weakened or damaged. Neurological insults from accidents, injuries, or other sources can impact executive functioning temporarily or long-term.

Executive dysfunction is often part of the presentation of neurodevelopmental disorders such as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Specific Learning Disabilities. Although executive functioning is thought to be the most impaired in the aforementioned conditions, it is also implicated in conditions such as anxiety, depression, and even medical conditions such as low blood sugar. Problems with executive functioning are often what bring families to seek help from psychologists, psychiatrists, or doctors.

Understanding the importance of executive functioning is the first step to facilitating its development. The ‘Practice Makes Perfect’ principle applies here. If a child has no experience planning for their day or organizing their materials, it is unlikely that he or she will simply arrive at this skill in high school.

From the time they are small, children should be encouraged to help with planning and organizing. A toddler may not be able to make a sandwich, but they can help pack a lunch. Likewise, a young child who cannot do their own laundry can sort laundry or help pick out clean clothes for tomorrow.

Children can also help with the planning and preparation for parties, events, and projects. Learning how to react when what we want is not available, what to do when we forget something important, and how to persist with the temptation of distractions are all valuable skills that adults need to afford children. Children can have fun while they help adults with household tasks and learn these skills. They can also work on these skills in their play.

Childhood games have been shown to improve the executive skills of preschool children. Games such as Simon Says, Red Light Green Light, and Mother May I all help children to practice attending, inhibiting impulses, problem-solving, regulating behavior, and regulating emotions. For older children, yard games such as Freeze Tag and Capture the Flag can be helpful. Board games are also great ways to develop flexibility, inhibition, problem-solving, and shifting. Some favorites for young children are Candy Land and Chutes and Ladders. These games are great for teaching flexible thinking by changing the rules. Some fun examples are to play the board backward or try to be the last one to cross the finish line! For older children, strategy games such as chess, Chinese checkers, or Risk may be helpful. Children and adults also tend to enjoy German-style or Euro board games. These games tend to minimize conflict and luck and emphasize problem-solving strategies. Some popular examples are Ticket to Ride, Settlers of Catan, Small World, and Dominion. These games require planning, problem-solving, shifting strategies, and many other executive functions to master despite relatively easy gameplay and moderate playing times.

In addition to practicing executive functioning skills throughout life, accommodations and supports for weak executive functioning are often helpful. For example, making lists, using sticky-note reminders, using alarms, and having organizational systems in place can help support executive functioning skills. There are several books available with excellent strategies for support. Some of my favorites are: Smart but Scattered: The Revolutionary “Executive Skills” Approach to Helping Kids Reach Their Potential by Peg Dawson and Richard Guare; The Explosive Child: A New Approach for Understanding and Parenting Easily Frustrated, Chronically Inflexible Children by Ross Greene, PhD; and The Asperkid’s Launch Pad: Home Design to Empower Everyday Superheroes by Jennifer Cook O'Toole.

Executive functioning skills take effort and experience to develop over time. Many services and providers exist for families requiring guidance to facilitate growth in their loved one’s executive functioning. The Stewart Center at The Westview School offers individual therapy to facilitate executive functioning in adolescents and adults, group therapy for fun skill-building in children, as well as parent coaching and case management to assist families in promoting these skills in their daily lives at home. For more information, contact 713-973-1842 or info@stewartcenterhouston.org.

--

Dr. Natalie Montfort is a licensed clinical psychologist with Montfort Psychology Associates. Dr. Montfort has over 20 years of experience working with children and adults with ASD and has training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (with children, adolescents, and adults), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Relationship Development Intervention, Social Thinking, behavior modification (including Applied Behavior Analysis), and education/educational assessment. Dr. Montfort graduated summa cum laude and as valedictorian of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Houston with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Psychology. She earned a Master of Arts Degree and a Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Clinical Psychology from Fielding Graduate University. Dr. Montfort completed her doctoral internship with the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and her post-doctoral fellowship at The Stewart Center at The Westview School. She obtained licensure as a Clinical Psychologist in 2016, and she and Dr. Ken Montfort launched Montfort Psychology Associates in 2020. Her areas of interest include assessment of children, adolescents, and adults; cognitive and behavioral differences in children with neurodevelopmental disorders; treatment of adoption-related issues; treatment of childhood trauma; and animal-assisted therapy. She also enjoys providing professional development, trainings, and lectures on these and other topics to a wide variety of audiences.

This blog post was adapted from the presentation given during WestviewEDU on Thursday, September 1, 2022. WestviewEDU is an education series presented by The Westview School for parents and caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. For a full list of WestviewEDU sessions for 2022/2023 academic calendar year, visit The Westview School online.

A Parent's Guide to Managing Therapy for Kids with ASD

There are many factors to consider when determining interventions and support for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). What works best? How often should we go? How many hours do we devote to this? What behavior or symptom do we target? Who provides this service? The list of questions is lengthy and can feel overwhelming. Here is a concise list of things to take in consideration as we determine the best supports for our children.

It Takes a Village

When it comes to therapy choices for your child, you don't have to make all these decisions on your own. One of the benefits of having multiple providers is that you can develop a treatment team. A treatment team is usually made up of the various providers working with your child. This may include their therapists, teachers, doctors, caregivers, and the individual themselves. Having a team of people on the same page regarding goals and treatment for your child helps immensely when deciding what approach to take, whether treatment is working, and what steps should be taken next.

No One Size Fits All

Because ASD is a heterogeneous disorder, it is challenging (if not impossible) to make blanket statements about what works best. We know from decades of research that behavioral interventions are often beneficial for individuals with ASD. Behavioral intervention is a broad category, though, and the delivery and duration of services may look quite different. When selecting an intervention, it is essential to remember that your provider should be able to explain why they are using a particular therapeutic approach with your child, what precisely they are targeting, and how data drives their decision-making.

When Needs Change, Therapies Should Too

When it comes to interventions or therapies and ASD, we often spend a lot of time talking about applied behavior analysis or ABA and social skills. But children often need other services like speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy. Sometimes we also need to develop skills to benefit from other interventions. For example, if our child has difficulty with behavior regulation or attending skills, they may not be ready for a group social skills program. We also tend to focus on early identification and intervention. Still, as children get older, priorities may change. There are other co-occurring conditions that families should be aware of, as these diagnoses may also require treatment or intervention. For example, many children and adolescents with ASD experience anxiety and/or depression. In this case, we may want to find a therapist with experience providing interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with modifications for ASD.

Ask an Expert About Medications

It is helpful to remember that sometimes individuals may need medication in addition to therapy. At this time, there are no FDA-approved medications that treat the core features of ASD. However, approved medications can address symptoms like irritability, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, sleep, etc. Decisions about medication can be complex and multifaceted. Medication is something families can discuss with their child's treatment team. Having multiple sources of input can help inform families and prescribers on the effects of medication. And just like with other forms of treatment, baseline and ongoing data collection should be an important component of decision-making with medication.

In summary, there are many different approaches to treatment for children with ASD. As children get older, our approach to treatment may change better to meet the needs of the individual and their family. Treatment may need to address other mental and behavioral health issues and ASD. There is no absolute or set plan to follow for treatment or intervention for individuals with ASD. And because there are so many options and choices, making decisions can feel overwhelming. Focusing on treatments with solid evidence can help guide families during these times. Communication with your child's treatment team can also help facilitate decision-making.

--

Anna Laakman is currently a third-year doctoral student in School Psychology at the University of Houston. She is originally from Little Rock, Arkansas, but returned to Houston from Southern California, where she worked at the Center for Autism & Neurodevelopmental Disorders at the University of California-Irvine as the Education and Training Director. Her B.A. is in Communication and Sociology from Wake Forest University in North Carolina. She also holds a master's degree in Special Education with a focus in Autism Spectrum Disorders from the University of Missouri-Columbia. Her previous work experience includes work at the University of Missouri Thompson Center for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in diagnostic evaluations, research, and training and education. Additionally, Anna previously worked at Texas Children's Hospital on the Simons Variation in Individuals Project. Her current research interests are in camouflaging in ASD and the female phenotype of autism.

This blog post was adapted from the presentation given during WestviewEDU on Thursday, November 4, 2021. WestviewEDU is an education series presented by The Westview School for parents and caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. For a full list of WestviewEDU sessions for 2021/2022 academic calendar year, visit The Westview School online.

7 Ways to Use Therapeutic Strategies to Work with Your Child at Home

If you have a child on the autism spectrum, it is more than likely that therapy sessions play a part in your monthly calendar. The types of therapy that specifically benefit your child may differ. However, it has been proven that therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder is beneficial to improve behaviors that interfere with your child's ability to learn and support the development of skills needed for children to care for themselves independently. As a parent, you can use therapeutic strategies learned from professionals to help you work with your child at home.

This is not a post about what therapy will work best for your child but one that offers therapeutic strategies you can use to work with your child at home. However, it is essential to make sure the therapy of choice for your child is effective. The best quality therapies have documented evidence of replicated positive effects and don't rely heavily on personal testimonials. Most importantly, you should be receiving parent support from your child's therapist to learn about ways to improve or sustain your child's progress.

The best ways to apply skills that your child has learned in the home are to:

1. Create functional learning opportunities. For example, if your child is working on requesting things they need, set up situations that will help them functionally apply the skills they are learning. Give them a bowl with no spoon or an empty cup with no juice. This will create the opportunity to apply their newly learned skills.

2. Turn mistakes into learning opportunities. Help foster independence and application of problem-solving skills by helping your child find solutions to the mistakes that they have made.

3. Establish and follow through with boundaries and consequences. Be clear with your expectations and do exactly what you say you are going to do. If you say, "First we need to clean up, then we will go to the park," then you should only take them to the park IF they cleaned up first. When you don't follow through with the boundaries you set, you unintentionally teach your child that they don't need to follow your instructions.

4. Reinforce attempts at independence. Reinforcement is the only way to increase the likelihood of them engaging in that independent behavior in the future. Since we want our children to be as independent as they can, we must reinforce their attempts at being independent.

5. Include language used in therapy in the home (and vice versa). Using the language or phrases that your child commonly hears will help promote generalization across settings, like the home and their therapy clinic.

6. Adapt accommodations for home use and portability. Make sure that you can bring any accommodations (ex: visuals, communication devices, sensory tools, etc.) that help make your child successful into the home and community.

7. Evaluate and care for your personal well-being. You will not be able to apply all the previously described strategies without taking care of your own mental, physical, and emotional needs.

Putting these therapeutic strategies into practice at home is a great way to reinforce your child's work in the therapy setting.

--

Jelisa Scott is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) and a Licensed Behavior Analyst (LBA) in the state of Texas. She received her bachelor's in Psychology from Louisiana State University in 2010, her master’s degree in Behavior Analysis from the University of Houston Clear Lake in 2014 and is currently in school to earn her doctorate degree in School Psychology from the University of Houston. Jelisa has been working with children with and without special needs since 2008 and has gained experience providing in-home ABA services, parent training, classroom consultations, navigating ARD meetings, decreasing severe problem behavior, improving verbal behavior, social skills training, and early childhood intervention.

This blog post was adapted from the presentation given during WestviewEDU on Thursday, October 7, 2021. WestviewEDU is an education series presented by The Westview School for parents and caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. For a full list of WestviewEDU sessions for 2021/2022 academic calendar year, visit The Westview School online.

Put on Your Oxygen Mask First: 5 Self-Care Strategies for Autism Parents

When it comes to parenting a special needs child, there are many things to consider: therapies, schools, medications, the list goes on. However, arguably one of the most essential therapeutic strategies to help your child is evaluating and caring for yourself. To have the physical and emotional energy to fulfill all the duties of a parent (especially an autism parent), you must make sure you are mentally healthy. How many times have we been on an airplane and heard the flight attendant advise, "in case of an emergency, secure YOUR OWN oxygen before helping others next to you." In the case of raising a child with autism, it is essential to "secure your own oxygen" before you can be expected to help your child. Parents who are stressed, feeling anxious about the future, or having depressed feelings about their child's current stage of development, are more likely to have trouble helping and supporting their child in the ways they need. If you really want to help your child, challenge yourself to make these parent coping strategies a habit:

1. Prioritize your self-care.

There's an old adage that says, "empty cups can't pour." Think about the things that fill your cup, and make time to prioritize them. Taking care of yourself is a selfless act because it sets you up to be in the best position possible to continue to advocate and care for your child's needs.

2. Engage with other Autism parents in the community.

You are not alone. Other parents and caregivers of children on the autism spectrum are going through similar situations as you. Expand your social circle to include support from other parents who understand what you experience. Shared experiences help build connections and can decrease feelings of depression, anxiety, and isolation.

3. Minimize anxiety by staying present.

The past is already done, and the future is not promised. Remind yourself to focus on today. When you worry about the future, you miss an opportunity to be grateful for what you have in the now. Be intentional about identifying what you are thankful for right now to help minimize your anxieties about the future.

4. Focus on your child's strengths.

Try not to focus on the negative. It is much more beneficial to focus on your child's strengths. There is no advantage mentally or emotionally to only see your child for the things they can't do. Knowing where your child's strengths lie and keeping them at the forefront can help you use that knowledge to supplement the areas where they need more support.

5. Plan time for fun.

All work and no play does not equal success. Sometimes your child (and you) need a break from it all. Taking time out from the hard work to laugh and play can improve your overall quality of life.

Remember, you are the most important person to your child, and they need you to be physically, emotionally, and mentally strong. Your child needs you to be strong enough to continuously advocate for their acceptance, accommodations, and inclusion within their community. Being strong doesn't mean that you won't have bad days. Improving your well-being doesn't mean that there won't be challenging times, but hopefully, these strategies will help you build healthy self-care habits and, in turn, will help you work better with your child at home.

--

Jelisa Scott is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) and a Licensed Behavior Analyst (LBA) in the state of Texas. She received her bachelor's in Psychology from Louisiana State University in 2010, her master’s degree in Behavior Analysis from the University of Houston Clear Lake in 2014 and is currently in school to earn her doctorate degree in School Psychology from the University of Houston. Jelisa has been working with children with and without special needs since 2008 and has gained experience providing in-home ABA services, parent training, classroom consultations, navigating ARD meetings, decreasing severe problem behavior, improving verbal behavior, social skills training, and early childhood intervention.

This blog post was adapted from the presentation given during WestviewEDU on Thursday, October 7, 2021. WestviewEDU is an education series presented by The Westview School for parents and caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. For a full list of WestviewEDU sessions for 2021/2022 academic calendar year, visit The Westview School online.

Memories of Our Mother: A History of The Westview School

To commemorate the fortieth anniversary of The Westview School, the sons of founder, Jane Stewart shared a personal reflection of their early memories of The Westview School and what the legacy of 40 years of Westview means to their family.

A little over forty years ago our mother, Jane Stewart, brought us (Joey, Alan and Steven) all together in the family room and told us she was starting a school for children with disabilities. She had been volunteering at The Briarwood School for a few years and a group of parents came to her and asked if she would consider teaching their children privately. These parents recognized our mother's compassion and love for all children.

Overjoyed that Jane could now offer personal attention and schooling to a population in need of facilities, she turned our “game room” into a school during the day. We have many wonderful memories of coming home from school and watching our mother teaching and caring for her students. Often, we would join our mother rather than playing video games. That time was always very special to us. The parents were ecstatic, and the children made remarkable progress during the time they were with our mother in our home. In fact, one of our mother's first students, whose doctor told her parents she couldn't be helped, years later not only graduated from high school but was also prom queen. Our mother knew that amazing things were in all of us.

After a long discussion, our mother and father, Joel Stewart, decided to purchase a small house on Westview Drive in the Spring Branch area of Houston to expand the school, its facilities, and number of students. The Westview School was born as was the beginning of one of the most successful and ground-breaking schools for children on the autism spectrum in the country. This was a defining moment for our mother, one which filled our family with pride and love. The growth of the school meant so much to her.

As The Westview School evolved, so did our involvement as a family. Alongside our mother was our father, who not only gave his generous support to the school but also brought with him his financial and regulatory acumen. Additionally, throughout high school, we volunteered our summers working various jobs doing maintenance, painting, and building on the school grounds. The most rewarding was when we volunteered as teachers' aids, running with the children on the playground, helping with art projects, singing Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes, and even happily laughing and getting soaked with the students on the slip and slide. These are the types of experiences that are so memorable and special to us.

The expansion of the school to its current location on Kersten Drive was one of the most incredible experiences of our lives. We were honored to have the late Barbara Bush preside over the opening ceremony. She graciously spent time with the students and recognized the importance of the school. This was an experience we will never forget. Most importantly, there would be a much larger school that could accommodate the growing population and could offer even more benefits to the students including a robust multidisciplinary team. Our mother made sure there was a small student-teacher ratio so that the current students received the same personal attention as her first students received in our game room.

The school expanded once again and added another building offering even more opportunities to students. Throughout the forty years, there have been many talented and brilliant individuals who have worked at the school and served on the Board to turn the school into what it is today. We are grateful that the school and staff have committed to the mission of our mom in providing a nurturing and positive environment. The teachers and the entire staff are dedicated and caring individuals. We continue to be impressed by the incredible work and enjoy watching the school and the students thrive.

Throughout our lives, we always felt that our mother was a miracle worker, and it really showed when she worked with children. Her caring, gentle and intelligent approach, based in love for each and every student, showed through at all times.

---

Joey Stewart is a feature film producer and restaurateur that lives in Dallas with his wife Laura, an interior designer.

Alan Stewart is happy to coordinate marketing and VIP programs for music, wine and NFL clients including Duran Duran, Matt & Kim, Westport Rivers Winery, and the Indianapolis Colts. He lives on a farm on the coast of Maine with his wife Lisa who is in the legal field.

Steve Stewart is a physician and Chief Medical Officer of a hospital in New Mexico and lives in Albuquerque with his wife Amy, a lawyer, and their two sons, Wells and Flynn.

Staying Safe at COVID-19 Level 1 in Houston

It seems like déjà vu that we are starting this school year with masks and health screenings again, but we’ve had some noteworthy scientific progress compared to this time last year. Hopefully these changes will make life a little more manageable and get us closer to being done with COVID!

There are so many things we were doing last year that we no longer need to do, since we know more about COVID-19. We don’t need to: wipe down our groceries with Clorox wipes, avoid takeout (no more missing out on Houston’s amazing restaurants!), or hide in our houses 24/7 (although sometimes it’s nice to catch up on Netflix!).

We just need to:

- Get vaccinated against COVID-19 when you’re eligible. When your children are eligible for the vaccine, get them vaccinated as well- currently only children 12 years and older can be vaccinated. Also, plan to get a booster shot when you’re eligible (currently, approximately 8 months after your 2nd dose of Pfizer or Moderna). If you have questions about the vaccines, check out our previous blog post on the topic.

- Maintain physical distance from others. While we have high rates of COVID-19 in Houston, try to stay away from others, even outdoors, and avoid large indoor gatherings.

- Wash your hands often. Soap and water is best, but hand sanitizer is a great option too.

- Wear a mask, especially in indoor space and even if you’re already vaccinated.

- Keep monitoring your personal and your family’s health. Watch for symptoms of COVID-19, even if you’re vaccinated. The most common symptoms of the delta variant COVID-19 are runny nose, sore throat, headache, and fever, which are also allergy symptoms in Houston! Take a COVID-19 test if you are experiencing any signs of illness.

- Maintain your hobbies and your support system. Now, more than ever, we need to keep up our spirits and keep an eye on our mental health.

As a community, we’ve banded together time and time again to face numerous challenges for our children. We know that this is one more trial that the Westview Wildcats are ready to meet. We are strong, flexible, and caring, and we can do this! Hopefully, we can help all of Houston get COVID-19 under control too, so we can truly put this pandemic time behind us for good.

Autism or Teen Drama? Tips to Manage the Teenage Years

The transition between childhood and adolescence can be a confusing and difficult time for children. Things are beginning to change on a mental, physical, emotional, and social level. Autism adds another complicated layer of development to these already challenging times for children. As a parent, you may wonder how you can best support and help your teen navigate these years. It comes with a myriad of questions: Are these behaviors normal? Should it be happening this early? How long will this last? Is this autism or hormones? Should I be concerned about a particular behavior? What can I do about it?

There are a few things to take into consideration. First, parents should determine whether new behaviors are actually due to autism or simply part of typical adolescent behavior. Also, parents need to consider if these changes reflect their teen’s individual personality and preferences. To make things more complicated, it could be a combination of all the above.

Typical Adolescent Behavior

To better distinguish between which behaviors are due to typical adolescent behavior versus autism adolescent behavior, let’s look at what typical adolescent behavior looks like:

- Physical changes include changes in hormones that can lead to new body hair or smells and increases in height and weight.

- Mental changes include developing more abstract thinking skills, using more logic and reason to make decisions, forming their own beliefs, questioning authority, and a heightened focus on physical concerns.

- Emotional changes include shifting moods quickly, feeling more intensely, and increasing risk-taking and impulsive behavior.

- Social changes include experimentation with different levels of social and cultural identity, increase in peer influence, awareness of sexual identity, and learning how to manage relationships.

Most children pass through this period of adolescence with relatively little difficulty despite all these changes. On an even more positive note, youth tend to be quite resilient when problems arise; this includes those with autism. Teens on the autism spectrum often thrive, mature, and increase their competence during this period of growth.

Tips For Parenting Your Teen on the Spectrum

Front Load Information: Our teens on the spectrum learn best when we can front-load them with logical and factual information. We need to be able to prepare them and teach them these life skills ahead of time. The truth is you will not be able to prepare them for everything but showing them the how, why, and what to do can support them through this transition. A simple one to tackle first is why we need to use deodorant or feminine products.

Share Experiences: Teens appreciate first-hand experience, so if you had difficulty navigating through a situation like theirs, then share your experience with them.

Answer Questions: Perseveration on any subject matter is common for children on the autism spectrum. When experiences are novel and uncertain, perseveration can sometimes increase and often cause heightened anxiety. This is not healthy or comfortable for any teen! Answering their questions, no matter how many questions there may be, will be helpful to your child. Also, offering solutions and assisting them in a calm, helpful, and consistent manner will convey that you care and validate their feelings.

Seek Outside Help for Your Child and Yourself: As parents, there is a tendency to tackle it all for your kids. However, during these adolescent years, it may be helpful and even more impactful for your teen to talk about these changes with someone other than you. This could be with a trusted family friend, relative, peer, or professional that the teen feels comfortable answering their questions.

You must also remember that you can build and rely on your support system to help you gain clarity from the fog of dealing with your teen daily. Parenting is hard, and these years with your child can be exhausting! Your community can offer support by letting you vent and sharing personal experiences. You are not alone.

Supporting and learning from each other is key to you and your kid's successful management of the teen years. This is true no matter how old they are. Parenting can be tricky. And life, in general, is not without its share of challenges. When parents and children work together to face changes head-on, we know that these struggles can produce perseverance, and perseverance helps build resilience for both you and your child.

As your child gets older and the teen years approach, it can seem daunting for parents, but as indicated above, there are ways to successfully support and help your teen through this time. If you want to learn more about individual or family therapy, please reach out to The Stewart Center at The Westview School. We are available to support you and your child.

Contact The Stewart Center at 713-973-1830.

--

Mimi Le, M.A., LMFT, LPC is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and a Licensed Professional Counselor. She provides therapy and consultations for adults, parents, siblings, children, families, and groups. She received her Bachelor of Arts Degree in Art History from Baylor University and earned her Master of Arts Degree in Family Therapy from the University of Houston – Clear Lake. She specializes in autism spectrum disorder, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, interpersonal relationships, and multi-generational and cultural matters. She also provides parent-coaching among her other duties as a Student and Staff Support Specialist at The Westview School.

3 No-Nonsense Answers to Common Questions on Special Education

Did you know that tigers have striped skin and not just striped fur?

Did you know that reticulated pythons are longer than green anacondas?

Did you know the formula for the volume of spheres is four-thirds times Pi times radius cubed?

Did you know that honey is actually just bee vomit?

There is a common saying within the autism community, "If you've met one child with autism, you've met one child with autism." Facts and insight collected from various students across various grade levels prove the point that we can always learn something from someone else. Like the students at The Westview School, these little nuggets of information are as different and varied as those who shared them.

With enrollment season upon us, the admissions department of The Westview School is busy fielding questions about the benefits of a private special needs education. Families are looking for the best fit for their children. The Westview School is proud to offer children on the autism spectrum a unique, specialized learning environment with outstanding educational and social opportunities. Some of the obvious benefits of a specialized special needs school include small classroom sizes and curriculum and instruction that is adapted based on each student's need. But there is much more that a school like Westview can provide a child that is not so easily quantified.

We asked our in-house experts, Becky Mattis, M.Ed., Admissions Director for The Westview School, and Mimi Le, M.A., LMFT, LPC, one of Westview’s Student and Staff Support Specialists, to weigh in on commonly asked questions prospective families have when deciding on a program like The Westview School. Their no-nonsense answers to the top three prospective family concerns about a private specialized education are supported by frank, heartfelt, and honest feedback from Westview students in elementary and middle school.

QUESTION 1: Will my child develop self-confidence?

One thing a parent of a child with autism learns very early on is that brains can grow. Developmental pediatricians and neurologists will tell parents, early intervention is the key, that a child's potential cannot be determined until they have an opportunity to learn. Children on the autism spectrum who participate in early intervention therapies and specialized schooling from an early age develop a growth mindset. The concept of a growth mindset was originally taught by Stanford Professor, Carol Dweck. She asserts that facing challenges, working hard, and learning from mistakes develops persistence and results in growth in intelligence and abilities. She further theorizes that people who develop a growth mindset at a young age are confident, resilient, and have a passion for learning. At The Westview School, you will frequently hear a teacher encouraging a student who is struggling with something say, "That's okay, you can try again." Instead of becoming frustrated when they make a mistake, we want our students to quickly regroup and try again.

Becky Mattis: Parents worry about self-esteem for their special needs child. The self-esteem impact that kids have when they are in a place that is meeting their needs, and they are learning and being successful is vastly greater than the negative impact that being in a place where their needs are not met, and they are feeling different and singled out.

Mimi Le: There is a vulnerability [at Westview] that you do not get in a neurotypical school setting. The vulnerability is that I am not the best at this. How can I get better? Both peers and teachers work together to help and encourage you. This may still happen in a neurotypical setting, but at Westview, we are very aware of it, and we make it part of each day, and so do our students.

When a student feels like they can excel at something new, they feel supported in their effort, and in turn, the other students in their class help that too. Students want to learn from the kid that is the expert on trains or the best at math. At Westview, there is never the social expectation to fit into the typical school social norms. There is no judgment. This builds confidence in a child when they are around others that support their expertise in something.

We asked Westview students, “What is your favorite thing about The Westview School?”

Jaden, Middle School: The teachers will go completely out of their way, will do anything they can to see their students succeed. They are always so nice and supportive, and I could not have any better teachers.

Thibault, Upper Elementary: I like this place because it provides a safe place. A safe place from bullies. [Westview] gives me a safe place to learn, and it achieves all its goals in doing so with all its students.

Noah, Middle School: I think The Westview School is a great place to be. The teachers, the classrooms, the fun things we get to do.

Cason, Middle School: My favorite things about The Westview School are the people, the academics. Look around [gesturing down the hallway]; this place looks pretty good.

Ruby, Lower Elementary: My teachers and everybody loves me and PE.

Theo, Lower Elementary: I have lots of friends to play with, and I learn things that I never knew before, and just like Ruby said, I like PE.

QUESTION 2: How will my child learn appropriate social skills without typical peer role models?

Becky Mattis: It is a common question for prospective parents, "Why not just put our child in a mainstream school to learn and observe social skills?" If our children could naturally pick up social and classroom skills from their neurotypical peers, they would easily fit into a mainstream setting. At The Westview School, we get excited when our kids pick up other behaviors because we can then use that as a building block for teaching and guiding our students toward a more appropriate social interaction. By virtue of the population, most of our students struggle with social skills, and because of that, we are intentional in working on the development of social skills throughout the day. The child is not being singled out by being pulled away to talk through those social situations. It is a learning experience for the whole class.

Mimi Le: When children on the autism spectrum are with others who are like them, they are more accepting of individuals with differences. When we put students together in a group or a class, we are looking at where are they are going to fit socially, behaviorally, and academically, so that they can learn something from another student. Where one student may be best at a particular thing, another student can learn from them. Everyone is learning from each other in those three different categories, which helps make them more well-rounded. All kids are different, autism or not. There is always something you can learn from someone else. The thought Westview puts in to placing our students helps to build a respect and appreciation for each other that they would not get in a normal neurotypical setting.

We asked Westview students, “What is something that your friends like about you? What makes you a good friend?

Jaden, Middle School: I am very persistent, and I will do what I can even if it must sacrifice quite a lot to get done what I need to do. I think that me knowing a lot makes me special because I get to teach people what I know, and I find teaching very fun.

Thibault, Upper Elementary: I am passionate, and I strive to work hard almost every single day. I am determined.

Theo, Lower Elementary: I like to run around and exercise a lot and play games. I like to play games on the playground besides tag, because my best friend Sid doesn’t like tag. I like it, but I want to play with him.

QUESTION 3: What if my child knows they are different?

We are all different, and differences should be celebrated, and all children should be taught in a way that most benefits them. In October of 2020, a teacher’s online post on why her neurotypical classroom looks like a special education one went viral. Karen Blacher, who has two children on the autism spectrum herself, found that students benefit greatly when classroom strategies are more focused on encouraging students to openly communicate, and expectations are adapted specifically to that child. Students are taught to both self-advocate and self-regulate.

Becky Mattis: We recognize that all kids are different whether they are on the spectrum or not. Each of our Westview children will discover the ways they learn best and how to then advocate for themselves. Self-advocacy is not only a skill they need for school but in life as well. Being accepting of the things that challenge them.

Mimi Le: Our kids become comfortable with who they are. It is okay to be different. Our kids develop an appreciation for themselves and each other. They are learning that their differences can be something they are proud of, and we foster that in the classrooms and through our conversations with parents. Our students will continue to give the world a new perspective on every aspect of life, and this new lens will lead to breakthroughs in the future.

With cultivating confidence in mind, we asked several Westview students, “What makes you special?”

Cason, Middle School: To be honest, I think I am pretty smart and good at gaming. I am probably the smartest in math. My brain works a little differently than everyone else. It can be good or bad in different ways.

Satvik, Middle School: I am a very tall person, and I am a hardworking boy.

Thibault, Upper Elementary: What makes me special is that I am different from everyone else, and it is like a whole different experience. Without these differences, I wouldn't have gone to Westview in the first place, and my sisters love me literally for who I am.

The Westview School’s mission is to provide a unique, specialized learning environment offering outstanding educational and social opportunities for children on the autism spectrum. We believe that children with autism spectrum disorder can grow and learn through a nurturing, positive, and happy environment that enhances their self-esteem. Building confidence, learning social skills and celebrating our differences is something that The Westview School builds into our daily curriculum.

If you think The Westview School could be a fit for your child, join us for our next Informational Session. The event includes discussions with our Admissions Director, Becky Mattis, about the student experience and program deliverables. Current parents will also be present to offer perspective and answer questions.

The Kids Are Alright: Words of Wisdom from Special Needs Siblings

It has been said that you spend more time with your siblings than anyone else. It is one of the most formative and longest-lasting relationships a person will have. It is estimated that by age 11, siblings have spent more than 33% of their spare time together. When one of those siblings is on the autism spectrum, it is possible that the amount of time together may not differ, but the sibling dynamics certainly could.